A Providential Encounter: Newman and the Passionists

A Providential Encounter: Newman and the Passionists

Fr. Adolfo Lippi CP

“Sir, don’t worry. One day Newman will be a doctor of the Church.” This phrase, spoken by Pope Pius XII in a private meeting with Jean Guitton[1], says everything about the esteem that this Pope had for Cardinal Newman. It was admiration similar to that of Pope Paul VI[2]. On numerous occasions Pope John Paul II referred to Newman, including in official documents. Among these it would suffice to cite Fides et ratio where he is quoted first among the modern thinkers who enlightened the relationship between the Word of God and human reason (No.74). The current Pontiff, Benedict XVI, has always been an admirer and a scholar of Newman[3]. However a fact that is most impressive is that, precisely after the publication of the encyclical Pascendi, during a period in which many modernists referred to Newman as their precursor, St. Pius X defended the orthodoxy and the sanctity of Newman.[4] And this year, on 19 September 2010, Newman will be beatified. This will be a moment of great joy for all those who read his works and his biography, and for those who have always been convinced about his sanctity, as well as about the profound intelligence of this man.

Newman and St. Paul of the Cross

In the Congregation of the Passion we wish to highlight the assistance that we Passionists provided for the entry of Newman into the Catholic Church. Normally, when we say this we think of Blessed Dominic Barberi and of the famous night of 8-9 October 1845 during which Dominic received Newman into the Church. The original historians, who were also closer to the facts, delighted in presenting the events of that night in a dramatic fashion, something which Dominic never would have done, being always very simple and loath to talk about himself. Alfonso Capecelatro, for example, who was an Oratorian and a future Cardinal, wrote about the event ten years after the death of Dominic: “Dalgarins invited a certain Fr. Dominic of the Mother of God, a Provincial of the Passionists, to go to Aston Hall in Littlemore, telling him that he was being called to a work in the service of God: and unwittingly, he agreed. He was always conscious that every delay could possibly result in some great harm to the office to which he called. However because of a terrible storm he set out in a covered coach. He endured five hours of driving rain and, as it so pleased God, completely exhausted he arrived at Littlemore at night. Without delay he entered in the solitary dwelling of those fervent men who were famous throughout England, and with great humility Newman fell at his feet, telling him that he would not move from there until he was blessed and received into the Church of Jesus Christ.”[5]

But there is more than this. I believe that before Dominic it was the Founder himself, St. Paul of the Cross, who impressed Newman. In Paul’s writings one is struck by several facts in which one perceives the presence of the Mystery, the action of God himself. Newman surely did not presuppose such an action nor to speak about it lightly, as was frequently done in other Christian settings. However he expresses his surprise at the fact that Paul of the Cross was moved to pray during his entire life for a far-away place such as England, with which he had no human contact. The novel Loss and Gain should be considered in this very significant point. It was published almost three years after the entry of Newman into the Catholic Church at the height of his enthusiasm at his conversion. In it, speaking about Paul of the Cross, Newman writes: “So it was, that for many years the heart of Father Paul was expanded towards a northern nation, with which, humanly speaking, he had nothing to do. Over against St. John and St. Paul, the home of the Passionists on the Celian, rises the old church and monastery of San Gregorio, the womb, as it may be called, of English Christianity. There had lived that great Saint, who is named our Apostle, who was afterwards called to the chair of St. Peter; and thence went forth, in and after his pontificate, Augustine, Paulinus, Justus, and the other Saints by whom our barbarous ancestors were converted. Their names, which are now written up upon the pillars of the portico, would almost seem to have issued forth, and crossed over, and confronted the venerable Paul; for, strange to say, the thought of England came into his ordinary prayers; and in his last years, after a vision during Mass, as if he had been Augustine or Mellitus, he talked of his “Sons” in England.”[6]

Except for some historians’ inaccuracies cited by biographers – the remainder always deals with a novel-from this description one can clearly see something that deeply impressed Newman.

Newman and Fr. Ignatius (George) Spencer

There is another Passionist, who undoubtedly moved Newman’s spirit: George Spencer, the Anglican pastor of a noble family (the same as Lady Diana) who had already entered the Catholic Church in 1830. He had met Barberi in Rome and was certainly influenced by him who had preached a crusade throughout Europe for the return of England to the Catholic Church. Years later Leo XIII spoke about St. Paul of the Cross and meetings that the Pope had with George Spencer, who became Fr. Ignatius of the Heart of Jesus, at the nunciature in Brussels.[7] George Spencer became a Passionist in 1846, two years before Newman published his novel.

It should be noted that Spencer, following his entry into the Catholic Church in 1830, stayed in contact with the Anglicans, especially with the more active members of the Oxford Movement, inviting them to pray together for unity, something that surely was not common at that time. Fr. Paulinus Vanden Bussche, who wrote an excellent biography of Spencer,[8] observed that Spencer would not have been in favor of Newman entering the Catholic Church since during the years prior to his conversion Newman had a very negative view of Spencer and the leaders of the Catholic Church since they supported the liberals in England and in Ireland. New contacts began following the transfer of Newman to Catholicism. The painstaking historical work of Fr. Paulinus is certainly very useful. In his biography one can understand that the relationship between Spencer and Newman during those years was very complex and consequently, difficult to summarize in a few lines. However, Neman and many others of the Oxford Movement accepted the invitation to pray for unity.

The novel Loss and Gain was written by Newman after his conversion. Undoubtedly Newman was thinking about Spencer when Charles, the protagonist of the novel, meets his friend Willis who had become a Catholic before him and had become a Passionist with the name of Fr. Aloysius. There is a phrase, inspired by St. Augustine, which reveals some of the admiration of Newman for Spencer and, at the same time, conceals it. Precisely on the last page of the novel, Charles, the protagonist, says to his friend Willis who had become a Passionist, that he admired the first fervor of the new convert: “No, Willis…you have taken the better part betimes, while I have loitered. Too late have I known Thee, O Thou ancient Truth; too late have I found Thee, First and only Fair.”[9]

Blessed Dominic Barberi and Newman

Finally we arrive at Dominic Barberi. Here, too, we can and we must point out Newman’s amazement before this humble Passionist. There are three quotations that must be studied in this regard. The longest is found in the novel that has already been cited where Newman, after having spoken about St. Paul of the Cross, then moves on to speak about one of his sons who arrived in England as he had foretold. He writes: “It was strange enough that even one Italian in the heart of Rome should at that time have ambitious thoughts of making novices or converts in this country; but, after the venerable Founder’s death, his special interest in our distant isle showed itself in another member of his institute. On the Apennines, near Viterbo, there dwelt a shepherd-boy, in the first years of this century, whose mind had early been drawn heavenward; and, one day, as he prayed before an image of the Madonna, he felt a vivid intimation that he was destined to preach the Gospel under the northern sky. There appeared no means by which a Roman peasant should be turned into a missionary; nor did the prospect open, when this youth found himself, first a lay-brother, then a Father, in the Congregation of the Passion. Yet, though no external means appeared, the inward impression did not fade; on the contrary, it became more definite, and in process of time, instead of the dim north, England was engraven on his heart. And, strange to say, as years went on, without his seeking, for he was simply under obedience, our peasant found himself at length upon the very shore of the stormy northern sea, whence Cæsar of old looked out for a new world to conquer: yet that he should cross the strait was still as little likely as before. However, it was as likely as that he should ever have got so near it; and he used to eye the restless, godless, waves, and wonder with himself whether the day would ever come when he should be carried over them. And come it did, not however by any determination of his own, but by the same Providence which thirty years before had given him the anticipation of it.

At the time of our narrative, Father Domenico de Matre Dei had become familiar with England; he had had many anxieties here, first from want of funds, then still more from want of men. Year passed after year, and, whether fear of the severity of the rule-though that was groundless, for it had been mitigated for England-or the claim of other religious bodies was the cause, his community did not increase, and he was tempted to despond. But every work has its season; and now for some time past that difficulty had been gradually lessening; various zealous men, some of noble birth, others of extensive acquirements, had entered the Congregation; and our friend Willis, who at this time had received the priesthood, was not the last of these accessions, though domiciled at a distance from London. And now the reader knows much more about the Passionists than did Reding at the time that he made his way to their monastery.”[10]

This description is very moving and we believe that it expresses better than any other testimony the debt of faith and piety that Newman felt toward Paul of the Cross, Dominic Barberi and the Passionists in general. Many times Newman expressed his amazement at events that could have only been divinely inspired. Could a young shepherd from Viterbo ever think of becoming a missionary in England? And furthermore, who would have thought this about a lay brother in a monastery? And even when he became a priest, under obedience, how could he ever have considered making other plans? And when he was finally able to leave the northern European continent, he had no plans for England? Even miracles happen. It is interesting to compare a totally British gentleman like Newman came in contact with a humble religious, remembering that in England he awkwardly dressed in mandatory civilian garb, with the great conqueror, Julius Caesar, imagining both of them on the shore of the North Sea, gazing longingly at the Island.

The second quotation is from a letter written by Newman to Phillips with his usual intellectual clarity and honesty: “If they [Catholic religious] want to convert England let them go barefooted into our manufacturing towns-let them preach to the people like St. Francis Xavier-let them be pelted and trampled on-and I will admit that they can do what we cannot…What a day it will be when God will make arise among their Communion saintly men such as Bernard and the Borromeo’s…The English will never be favorably inclined to a party of conspirators and instigators; only faith and sanctity are irresistible.”[11]

Benedict XVI made this comment about the conversion of Newman: “The verses that Newman composed in Sicily in 1833 are noteworthy: ‘I loved to choose and see my path; but now Lead Thou me on!’ For Newman the conversion to Catholicism was not motivated by personal desire or by subjective spiritual needs. This is what he expressed in 1844, when we can say that he was still on the brink of conversion: ‘no one could possibly have a more unfavorable opinion of the present Roman-Catholic state than do I.’ Instead, what was important for Newman was the duty to adhere more to the recognized truth than his own desires, even including the conflict with his own feelings and with the bonds of friendship and common formation.”[12]

What happened between 1844 and 8 October 1845? The miracle that occurred was the appearance of the Catholic religious who arrived barefooted in the manufacturing towns of England and who preached liked Francis Xavier and Newman could not turn back. Dominic himself, a man with great willpower, abandoning all his mortifications, described his English experience in this way: “[There were] innumerable crosses and difficulties and such that at times I saw myself at the very end and almost at the point of turning back. I am certain that many people would want to come here; but if they saw what I saw and had to suffer what I suffered, almost all of them would change their mind. Oh, my God! My God! How much I have to suffer! I have been preparing for this for 28 years and I see that this preparation is not enough. The divine will alone sustains me: I am here because God has wanted this from all eternity. Blessed be his holy Name. This is my only strength.”[13] In fact, on that mission, Dominic quickly became ill and he died at the age of 57.

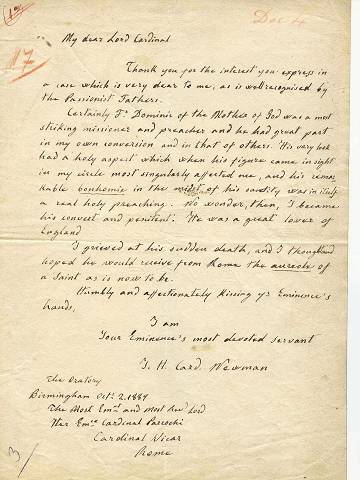

The third selection that I wish to quote is much later that the others. It forms part of the deposition that Newman made concerning Blessed Dominic in 1889, one year prior to his own death. It was the deposition that he made to Cardinal Parocchi, the Vicar of Rome, who at his own initiative promoted the causes of the beatification of Dominic and other Passionists Servants of God. Newman, already a Cardinal, wrote:

“My dear Lord Cardinal, Thank you for the interest you express in a case which is very dear to me, as is well recognised by the Passionist Fathers. Certainly Fr. Dominic of the Mother of God was a most striking missionary and preacher and he had great part in my own conversion and in that of others. His very look had a holy aspect which when his figure cam in sight in my circle most singularly affected me, and his remarkable ‘bonhomie’ in the midst of his sanctity was in itself a real holy preaching. No wonder, then, I became his convert and penitent. He was a great lover of England. I grieved at his sudden death, and I thought and hoped he would receive from Rome the ‘aureola’ of a Saint as is now to be.”[14]

The work of Dominic with Newman and the new converts of Littlemore was not limited to receiving them into the Church. The esteem that Dominic had even before the conversion of Newman for the little group of Littlemore was impressive. He touchingly and lovingly wrote to Dalgairns in September 1845: “Dear Littlemore, I love Thee! A little more still and we shall see happy results from Littlemore. When the learned and holy Superior of Littlemore will come, then I hope we shall see again the happy days of Augustine, of Lanfranc and Thomas. England will be once more the Isle of Saints and the nurse of new Christian nations, destined to carry the light of the Gospels coram gentibus et regibus et filiis Israel”.[15]

Dominic worked with the converts especially during the early years. There were various reciprocal visits. Dominic counselled them to remain united. Concerning the need for holy men who would work with him in his very difficult work in England, he did not try to gather them on his own. In a letter that Newman wrote to A.J. Hammer in 1850, when unfortunately Dominic had already died, a victim of fatigue, there is clear evidence given by Newman regarding the selfless efforts of Dominic: “I have to tell you something. If there are those who do not look for self glory it is the Passionists. Dear Fr. Dominic never made advances-he was very reserved-whatsoever were the needs of the novices he offered his most attentive and continual effort. Without a doubt you will find the same in Fr. Ignatius (Spencer).[16]

In Dominic there was that respect that made the English aristocrat Newman say that he was a very refined man who was also able to faithfully discern the will of God while being be objective and unbiased, something that always leads to growth and new life. Dominic observed-as noted by Federico Menegazzo, one of his most scholarly biographers-that “during all of early years of their [religious] life they specialized in university studies and this did not put them on the road of popular preaching, alternating with a full schedule of choral prayer and penitential practices.”[17] Later he himself counseled them to enter the Oratory of St. Phillip Neri.

Newman considered Dominic to be a “simple and ordinary man”, but also “intelligent and astute in his state of life.”[18] He wrote: “He was an intelligent and astute man, yet spontaneous and simple like a child; and he is especially kind in his dealings with the faithful of our communion. I wish that all people had as much charity as I know that there is in him.”[19] At the time of his entry into the Catholic Church, Newman had a notable problem with the publication of one of his most important works, recently completed but still unpublished: the Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. How would it be viewed by the Catholics since it was a work that was written while Newman was still an Anglican? Among the Catholics who would immediately judge it positively was Dominic. Newman wrote about him to James Hope: “A prepossessed person, but a shrewd and a good and a deep divine, Father Dominic, is very much pleased with it.”[20] This agreement about a very delicate matter-the development of dogmas-revealed a much more profound agreement between two spirits, although very different in their formation.

The ecumenism of love

The words of Newman quoted above, chosen from among many others, would be sufficient to highlight the importance of the love that existed in the relationship with the separated Christians. The Cathedra, Gloria Crucis and the magazine by the same name, proposes to dedicate a year-2010, the year in which the great Cardinal theologian will be beatified-to Newman, Dominic Barberi, Ignatius Spencer and their friends in the context of what Newman called the second Spring of English Christianity. Some of the works of Newman will be reprinted, in particular the masterpiece of ecumenism of love, i.e. the Letter to the Professors of Oxford – Cor ad cor loquitur, which was the motto chosen by Newman for his Cardinal’s coat of arms. And Dominic wrote: “Nihil est tam arduum quod verus amor non audet… Multis abhinc annis (plusquam quinque excesserunt lustra) Deus dignatus est pro sua bonitate amorem in corde meo accendere erga fratres meos praesertim anglos: pro quorum salute ab illo tempore nunquam orare destiti… Utinam Deus mihi concedat vitam meam pro vestra salute profundere!”[21]

Until almost the time of Vatican Council II, we should acknowledge and state that the relationships between the separated brethren of the various churches was characterized by notable hostility. When he was an Anglican, Newman himself was outspoken against the Papists. Yet Dominic loved; he loved them; he uniquely loved them; he loved them with an ardent love. It seems that he was the first to use the term separated brethren.[22]

In addition to the historical reports summarized here between Newman and Dominic, we should now proceed to study the basis of the same mind set that existed between Barberi and Newman. At this point Dominic’s approach to philosophy and to theology could prove to be very important. It is a topic that is yet unexplored. There are only a few, meager publications of the works of Barberi that can offer some material for further study of this topic. Perhaps this is the time for a more in-depth study.

In: Passionist International Bulletin, N° 23, June-Settembre 2010, 7-12

[1] Cf J. Guitton, Dialoghi con Paolo VI, Rusconi, Milano, 1986, 146.

[2] Cf C. Siccardi, Paolo VI, il papa della luce, Paoline, Milano, 2008, 214.

[3] Cf for example, what he says in a recently published document: J. Ratzinger – Benedetto XVI, L’elogio della coscienza. La Verità interroga il cuore, Cantagalli, Siena, 2009, 15-22.

[4] Cf Letter of 10 – 03 – 1908 Tuum illud opusculum, (Acta Pontificia, VI, (1908), 176).

[5] Newman, la religione cattolica in Inghilterra ovvero l’Oratorio inglese, Desclée, Tournai, 1886, 146-147. The Notice biographique du D. Newman par Jules Gordon states that he arrived at 11:00 PM in Littlemore and that he was standing near the fire to dry his clothing when Newman entered and asked him to be received into the Catholic Church. Newman also corroborates that he spent the night making his general confession.

[6] Newman, John Henry, “Loss and Gain, the Story of a Convert”, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1906, p. 416.

[7] Cf Amantissimae voluntatis ad Anglos Regnum Christi in fidei unitate quaerentes, in Enchiridion delle Encicliche, EDB, Bologna 1997, 1702-1703: “Quo enim tempore belgica in legatione versaremur, oblata nobis consuetudine cum Ignatio Spencer, ejusdem Pauli sancti a Cruce alumno pientissimo, tunc nempe accepimus initum ab eo ipso, homine anglo, consilium de propaganda certa piorum societate, rite ad Anglorum salutem comprecantium”.

[8] J. Vanden Bussche, cp, Ignatius (George) Spencer Passionist (1799-1864) Crusader of Prayer for England and Pioneer of ecumenical Prayer, Leuven University Press, 1991.

[9] Loss and Gain, cit., p. 420.

[10]Loss and Gain, cit., pp. 412-414.

[11] Letter of Newman to Phillips, quoted by Fr. Federico, Il Beato Domenico della Madre di Dio, Passionisti, Roma, 1963, p. 292.

[12] J. Ratzinger- Benedetto XVI, L’elogio della coscienza. La verità interroga il cuore, Cantagalli, Siena, 2009, 18.

[13] Letter to Fr. Felice, 10 april 1842, reported in Federico, op. cit., 319, n. 5.

[14] Letter quoted by Fr. Federico, op. cit., 397-398; cita Proc. Ord. Rom.,230.

[15] Letter quoted in Fr. Urban Young’s, Life and letters of the Ven. Fr. Dominic (Barberi), London, 1926, p.256.

[16] Letters and Diaries of J. H. Newman, by Dessain, London, 1961, XIII, 389.

[17] Op. cit., 389.

[18] Parts of a letter to Wilberforce, quoted by Fr. Fabiano Giorgini, in Introduzione a Domenico della Madre di Dio (Barberi), Lettera ai professori di Oxford. Relazioni con Newman e i suoi amici, CIPI, Roma, 1990, 29.

[19] Letter to Bowden, Ivi, 30.

[20] Letters…, cit., XI, 76.

[21] Dominic of the Mother of God (Barberi), Letter… cit.,. 63, 87 (

“Nothing is as powerful as authentic love. Many years ago (more than twenty-five years have gone by), God in his goodness, deigned to make love for my brothers and sisters burn in my heart, especially the English. And since that time I have not ceased praying for their health…May God grant that I may even give my life for their salvation!”)

[22] Cf F. Giorgini, Introduzione a Lettera… cit., 18 ss.